The hell of painful periods

“You’re normal, unfortunately that’s what being a woman is,” the first gynecologist I saw told me, scribbling a prescription on a piece of paper for stronger anti-inflammatories for my menstrual pain.

How do you want a woman to feel confident, listened to, reassured, when some gynecologists do not even take the time to listen to her, to examine her in order to discover the origin of her ailments?

I have always had menstrual pain to the point where I sometimes missed school and work, finding myself walking back and forth, hunched over between the bed and the bathroom to vomit. Only the hot or even burning shower could relieve me in part. Medication? They all made me nauseous and ended up at the bottom of the toilet bowl barely ingested.

Month after month, year after year, I had ended up getting used to it while apprehending the arrival of these “damn English”. If that was what being a woman was, then I had to be strong mentally and physically because the hardest thing to come was giving birth, right?

The onset of symptoms

During my 31st year, in 2019, I noticed changes in my menstruations; they were more abundant. I was changing sanitary napkins every hour which forced me to switch from regular pads to night ones. The blood clots were literally pushing the tampons out. As I had seen the gynecologist a few months before and he had told me that I was “normal”, I attributed these changes to the account of “old age”, surely part of the transition to my thirties.

Every month, I lived with these new periods, I adapted my outings, I changed regularly; I woke up several times a night only to notice the accidents on the sheets. It had become my new monthly routine.

A year later, August 2020, I started having a feeling of heaviness and pelvic burning, I had frequent urges to urinate at night, a small abdominal bump appeared when I lay on my back, and lower back pain, which had appeared a few months earlier, was becoming more and more bothersome. The stress at work linked to the Covid, and the fatigue due to the preparations for my move from Montreal to Saguenay, meant that I preferred to wait until I was settled in my new region before consulting.

The diagnosis

We are in early October 2020. I was able to get an appointment at a clinic fairly quickly; after a few questions, the doctor thinks it is a gynecological problem.

“But are you sure you’re not pregnant? Your uterus is very big, could this be an ectopic pregnancy?” she says to me in amazement.

I didn’t know what to say to her, I was so shocked. She then prescribed me complete blood tests as well as a urinalysis. The pregnancy test was negative, but I had an iron deficiency anemia caused by my heavy monthly blood loss. So that was why I complained all the time about being tired, that I was out of breath after the hikes. There followed three months of iron supplements and monthly blood tests while waiting for a gynecological appointment.

At the end of October, I have an appointment at the hospital for a TACO (a kind of abdominal scan): “9 cm mass suggestive of an intramural or submucous myoma which deforms the cavity endometriosis versus a straight ovarian lesion. A pelvic ultrasound in gynecology is recommended as soon as possible.”

It was during this time that the Vivre 100 Fibromes (Live without Fibroids) association was of great help to me, my spare wheel in this maze of information. Even before having my pelvic and vaginal ultrasound and my appointment with the gynecologist, I was able to understand my symptoms, the ailments that had lasted for all these years, and managed to put the puzzle together: menstrual pain, bleeding , pelvic pain, pain during intercourse, fatigue, lower back pain, bloating, the little bump… everything was linked to this fibroid, the ”invader” as I had nicknamed it. Thanks to the association, I had all the keys in hand to make an informed decision about the management of my fibroid.

Surgery or HIFU?

At the beginning of December 2020, the gynecological appointment and the ultrasound finally arrive. My legs, jaw and voice were shaking so much I felt helpless and stressed. But for the first time, I felt listened to and understood. The gynecologist decided to put me on the priority list of her surgeries and explained to me that the intervention was called a myomectomy by laparotomy, that she was going to make a small incision like a cesarian section and remove this ” snowball ” which would in any case prevent any fetus from developing as the fibroid was presently deforming the uterus. Seeing as she had never heard of HIFU, she left me free to do my research while keeping me on her priority list.

Following the precious advice of a fibromella, I immediately put together my file for the HIFU and sent everything to Bordeaux at the end of December. Around mid-January, I receive the answer: in my case, only surgery is possible. I was both disappointed with the response, relieved to have had a second opinion, but also proud to have followed through with my efforts without any regrets.

D-day

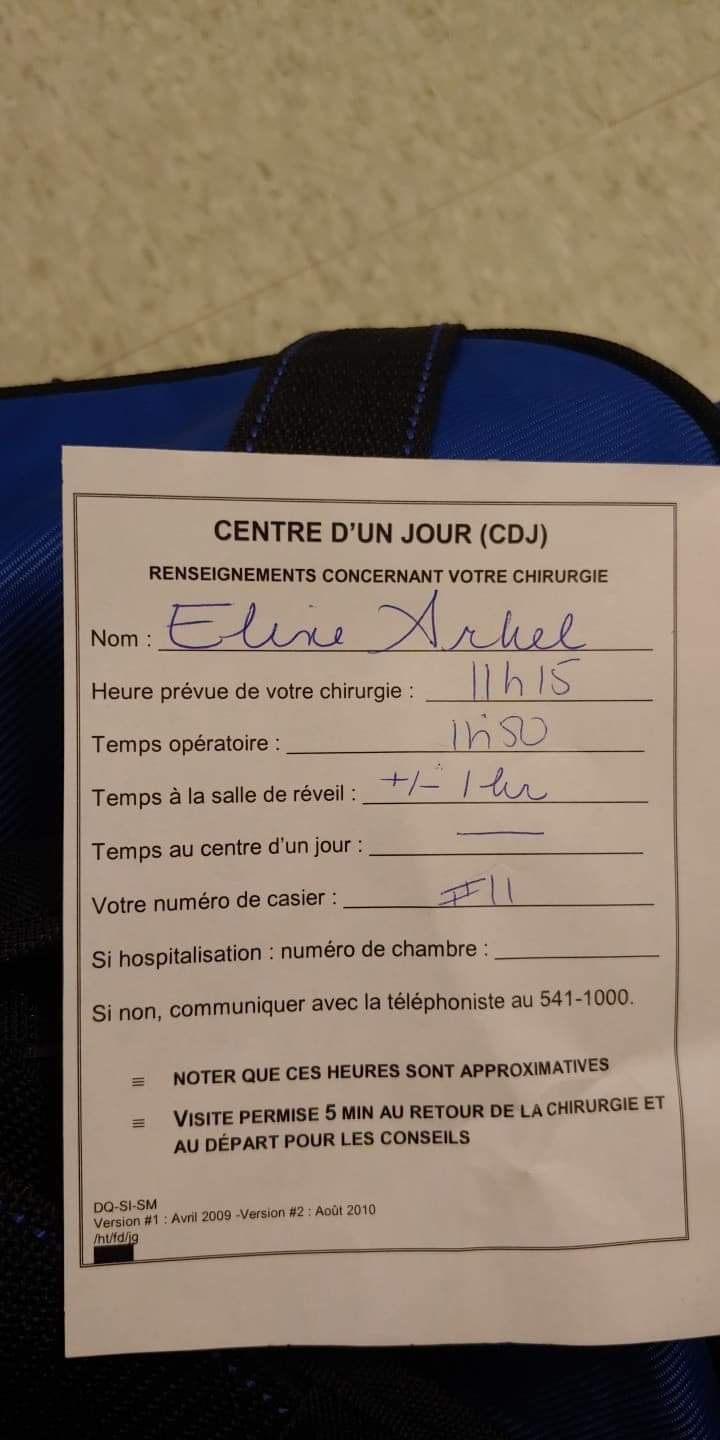

On March 4, 2021, I received the call for my surgery.

On March 8, Covid screening and pre-operative examinations.

March 9 is D-Day. After a final blood test, and once changed into my surgery gown, I head to the operating room with the nurse where the surgeon, the resident gynecologist, the anesthesiologist, and the respiratory therapist are waiting for me. Everyone introduces themselves and is kind to me. The nurse asks me to explain in my own words the intervention that I will undergo: “a caesarean section but instead of taking out a baby it is a mass that they will remove from me”. The gynecologist then approaches me and asks me if I am ready. I answer: “Do I really have a choice?” She reassures me by telling me that she will do everything in her power to make sure everything goes well. Those are the last words I remember before I fell asleep. The surgery lasted approximately one hour and thirty minutes.

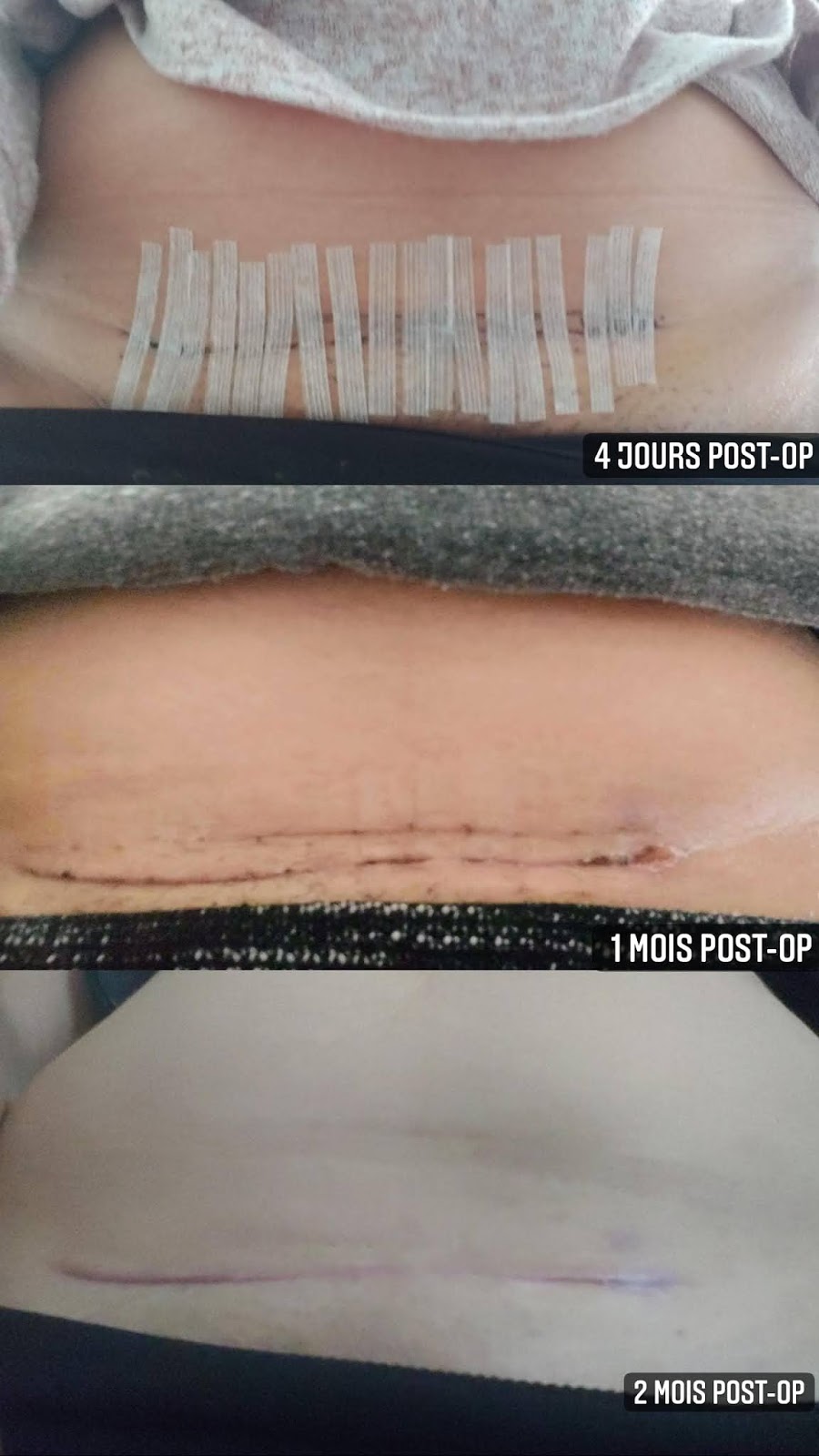

I wake up quietly with some nausea. The nurse injects me with an anti-nausea and 1 hour later I am stable enough to transfer to a room.

I stayed in the hospital for 3 days with a urinary catheter, intravenous fluids, and a small morphine pump to control the pain. To tell you the truth, after all these years of suffering, I was somehow mentally and physically conditioned: the post-operative pain seemed more bearable to me.

“2 months of work stoppage, 1 month without sexual intercourse, 6 months without trying to get pregnant, and scheduled delivery by compulsory caesarean if I become pregnant”.

These are the doctor’s recommendations upon discharge from the hospital.

The return home was difficult, but my boyfriend was there for all the small, innocuous daily actions: walking, getting up, sitting down, going to the bathroom, getting dressed, putting on my shoes. But day by day, we saw a marked improvement and I gradually regained my autonomy.

Conclusion

Although surgery can be risky, the hardest thing for me has been the wait: waiting for a diagnosis, living in uncertainty, not knowing what I had for weeks or months. We invent scenarios, we play Dr Google while doing research on the internet. We create our own fear and anxiety. I think I was still fortunate enough to come across the right people, at the right time, to take charge of caring for me, but there is still one thing that bothers me and makes me react:

If we know that fibroids are hereditary, that women past 30 who have not had children are more likely to have them, then why not do preventive examinations in the same way as mammograms? Why wait for symptoms to appear or worsen to hear about it from doctors, but also from those around you, as if it were a subject that is taboo?

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.